Williamson Avenue Underpass

Since the arrival of the first steam engine in 1881, many wagons and automobiles were involved in accidents while crossing the railroad tracks in Winslow. Dedicated on December 15, 1936, the Williamson Avenue Underpass has allowed cars and pedestrians to safely avoid the tracks, and trains to cross U.S. Highway 87, ever since.

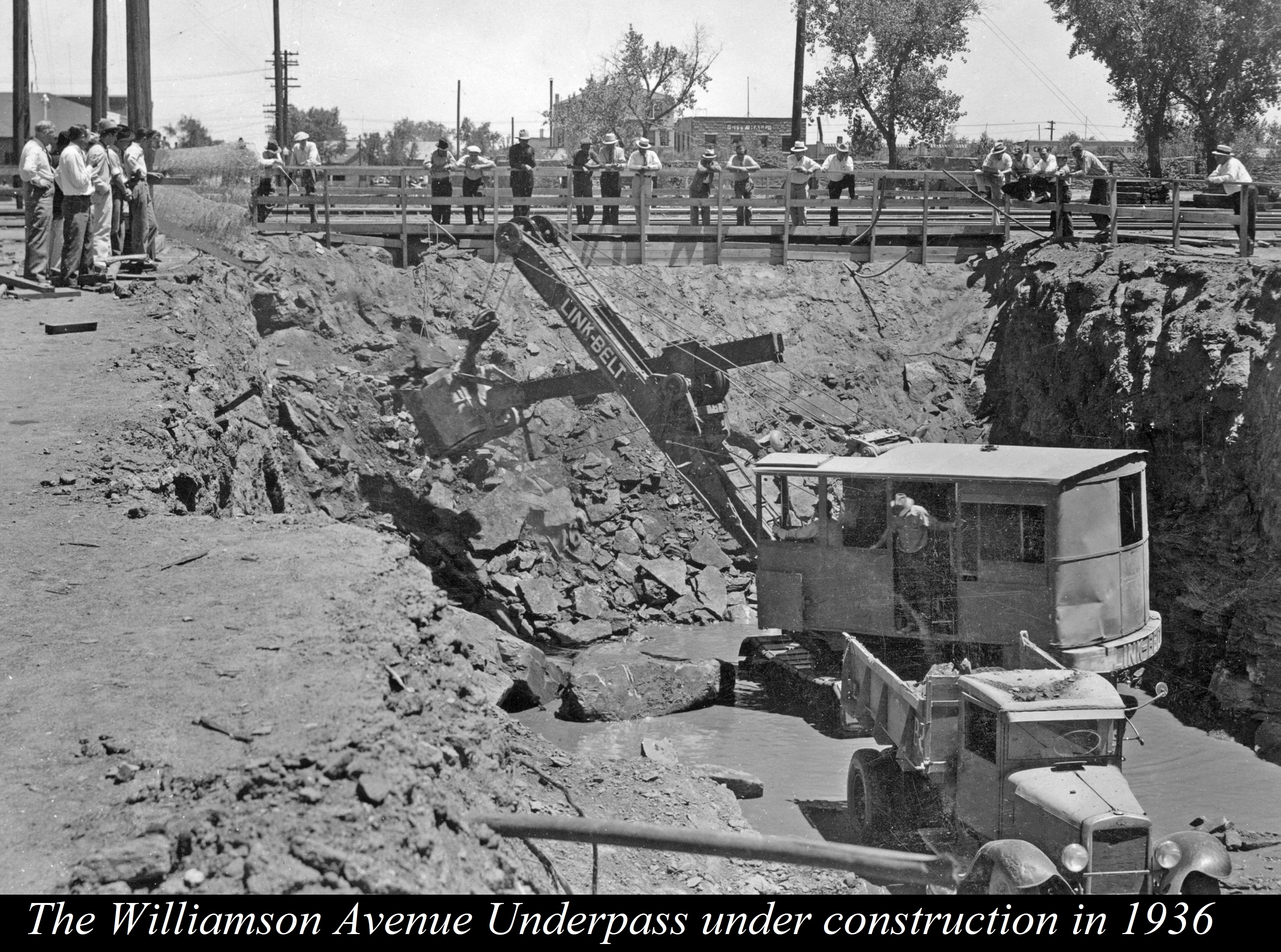

The Williamson Avenue Underpass was a cooperative project of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, the State of Arizona, the City of Winslow, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). A New Deal program in response to the Great Depression, the WPA cooperated with communities nationwide by employing local workers on relief to construct public works and buildings. The local men most responsible for bringing the WPA project to Winslow were City Engineer Frank Goodman, Chamber of Commerce President J.A. Greaves, and Chamber Secretary Walter Lindblom.

The contract went to the R.C. Tanner Construction Company of Phoenix for an estimated $150,000 (over $3,370,000 today). The project took eight months and 70,000 WPA man-hours to remove 14,500 cubic yards of earth, pour 3,000 cubic yards of reinforced concrete, and place 180 tons of steel in the ceiling and walls.

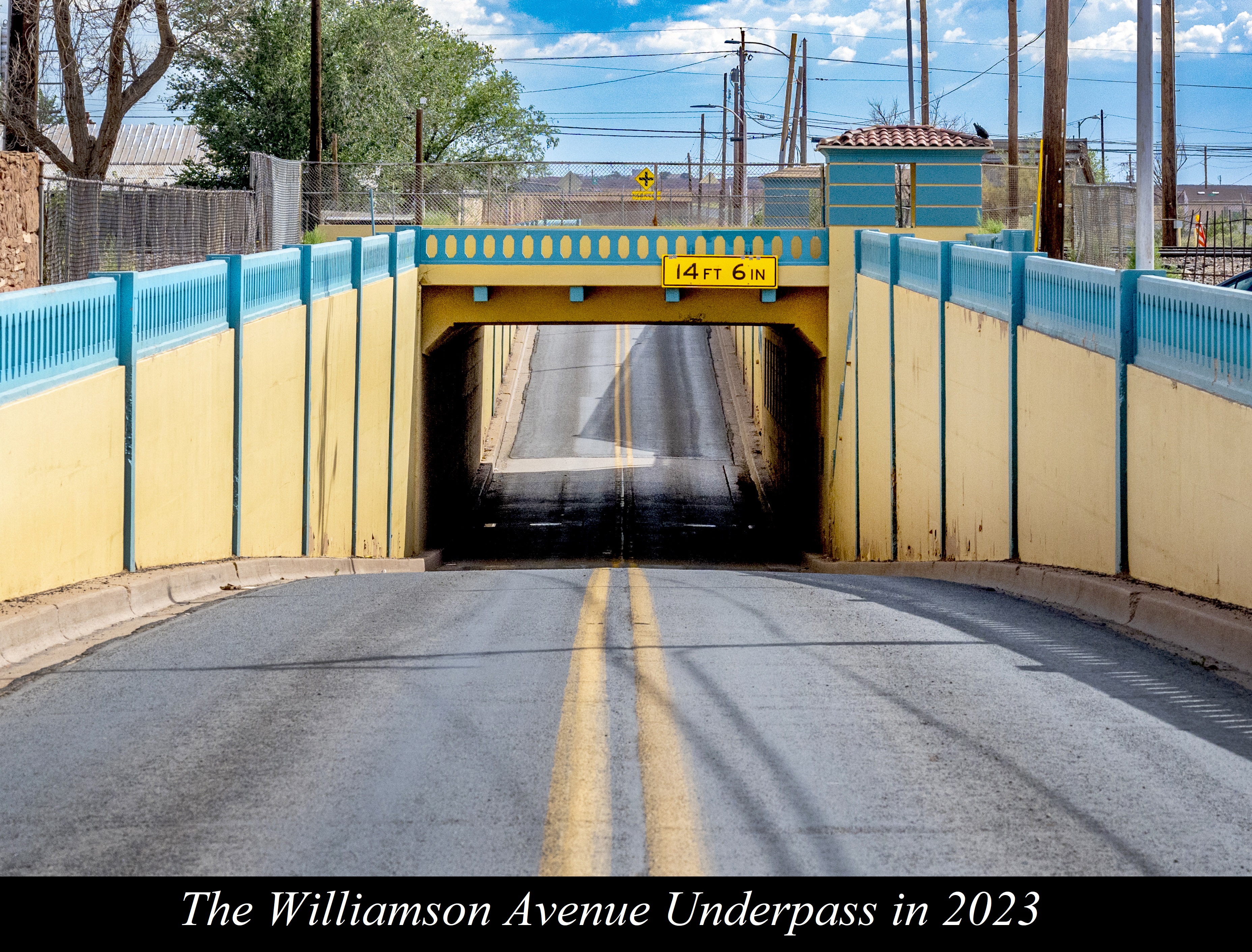

The underpass’s architecture displays Mission Style detailing of pierced parapet walls and guardrails, curved and corbeled bulkhead brackets, and a Spanish tile-roofed corner tower. Nearby, two concrete-and-steel pylons with the word "subway" on all sides marked the location of the important crossing. (One of those pylons was found in the surrounding desert decades later and returned to the City of Winslow, which reinstalled it in its original location in August 2019.)

Over 2,000 people attended the grand opening of the Williamson Avenue Underpass on December 15, 1936, when they heard remarks by local and state officials and a performance by the Winslow High School Band. Arizona Highway Commission Chairman Shelton G. Dowell stated that, "Having seen this structure for the first time since it was completed, I want to compliment and congratulate each man, from the contractor and highest engineer to the lowest cement worker's apprentice, for having turned out such a work of beauty and engineering. I am proud and happy to be able to present this underpass to you, the Honorable Mayor of Winslow, and trust that it may always be the vital factor in the saving of lives and time that it was intended to be." The Williamson Avenue Underpass was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.

Entry submitted by OTM Director Ann-Mary Lutzick. Visit the Old Trails Museum to discover more of Winslow’s rich history: www.oldtrailsmuseum.org

Tess Kenna reports:

Back in 1972, a young woman discovered an unusual object out in the high desert north east of Winslow. She told her family, the Kincaid's about it and they tried to find it several times, but could not.

Then in 1992, someone in the family came across it finally. This object was somewhat of a curiosity as it was a large and old pillar or concrete and steel with an ornate design that spelled out the word 'subway' on all four sides. Many Winslow residents that knew about it wondered because they know that Winslow used to be a bustling and prosperous town of high distinction on the old passenger line and highway, but never in Winslow was there ever an underground train. The nearest subway by the modern interpretation of the word is in Los Angeles, Calif. What was this subway pylon doing out in the desert near the Navajo Reservation?

Winslow Mail archives from 1935 and 1936 describe the style for the Winslow WPA projects at the club house and underpass in kind to La Posada that open six years before. Columbus Giragi, the former editor, publisher and reporter for the Winslow Mail described in '36, the Winslow Underpass as having Spanish-style architecture with painted tan concrete to look like adobe, a Spanish tiled roof tower, and parapet walls and guardrails. The subway pylon was the finishing touch to identify this important corner in Winslow, where train passengers, Harvey Girls, military troops, Southside/Coopertown residents and railroad works could then safely cross to downtown Winslow. Travelers and commerce were connected from Route 66 in northern Arizona to the new Highway 87 south to the forest and eventually Phoenix, Ariz.

The Winslow Underpass cost $150,000 to complete. The RC Tanner Construction Company of Phoenix managed its construction. WPA labor provided about 70,000 man-hours. The Arizona Department of Transportation has since taken inventory of the Winslow Underpass, and have it recorded as being in "good condition."

Back on Dec. 15, 1945, Winslow planned to have a dedication at the underpass and parade to the golf club house. The whole town was told to shut down at 2pm and attend. "Not since the National Rifle Association parade has such a large crowd turned out to a program in Winslow," Giragi wrote. "This being due to the fact that it was a 'California Sunday' and many of the railroad men were at home."

Next to the subway pylon, S.G. Dowell, chairman of the Arizona Highway commission said the following in his dedication speech: "I feel particularly honored because it has been erected by the City of Winslow, that gateway to those natural wonders of the world, the Grand Canyon and the Petrified National Forest," he said. "I also feel that your city is destined to become a Mecca for the tourist in their exploration of the virgin country to the north."

Dowell continued: "From 1914 -- 1918, the countries of the world engaged in a bloody and inhuman war to make the world safe for democracy. Perhaps the succeeded, perhaps they failed. But we at the highway department of Arizona, wage eternal and silent warfare to make the highways safe for humanity...The highway fatalities up to date which already exceed those of all wars the U.S. has ever engaged in, show a decrease this year. This is the first time such a thing has happened since advent of automobiles. But, the record in Arizona is a far different thing."

"We in Arizona have shown an increase in fatalities for another year," he said. "Perhaps it is because we are a baby state with a steadily increasing population with a hangover from the old 'devil-may-care' attitude of our early settlers."

"To the Barney Oldfields, who race with a train to the crossings, we apologize for having built this edifice and taken away half the pleasures of life away from them," Dowell said.

It was something that people of time said had to be done for safety's sake.

Ironically, Winslow resident Jim Weldon remembers when he was a boy in downtown Winslow that a train pulled up to La Posada and dropped off some troops on leave or en route. A soldier came running towards downtown Winslow, perhaps towards the many bars then. It was speculated he did not know of the remarkable new underpass and must have though of it as the old ground level crossing. Weldon said the underpass was between the man and downtown and the man all of a sudden jumped the small concrete barrier and fell to his death on the new road below. Many people in downtown ran to see the commotion and Weldon recalled standing near the subway pylon during that time.

Few Winslow elders spoken to, remember anything about the underpass or subway pylon. It is not yet known when and why these pylons were taken out and dumped.

George Stegmeir, of Winslow but now living out of state, a few years back when he lived in Winslow had talked with his friend about the subway pylon. Both men did remember it and a few people had known of its whereabouts in the desert. Stegmeir and Kenny Wetzel had gone out to the desert location with a large truck and crane to lift the historic object. They loaded it up and Stegmeir dropped it off at an out-of-the-way location in Winslow, where it sat until he transferred ownership of it to the Old Trails Museum.